Python's Reproducibility Crisis: And How We Fixed It for Open Science Education

Sep 15, 2025 • Open Science

What I learned building tested Python environments at scale—and how it shaped the way we teach open science at pyOpenSci today.

The problem nobody (or everybody?!) talks about

We obsess over reproducible analysis, version control, and open data. But there’s an earlier barrier that kills scientific momentum before research even begins: installation friction.

If a scientist can’t install your tools, your open science dies on arrival. And the same is true for open education lessons and tutorials, too.

I learned this the hard way when I switched from R to Python while building data science education programs. What started as a teaching frustration became a lesson in scientific infrastructure—one that shapes how we approach Python education at pyOpenSci today.

When installation becomes a barrier to science

Picture this: You’re teaching a workshop to ecologists who need to process spatial data. They’re motivated. They’ve carved out time. They’re ready to learn.

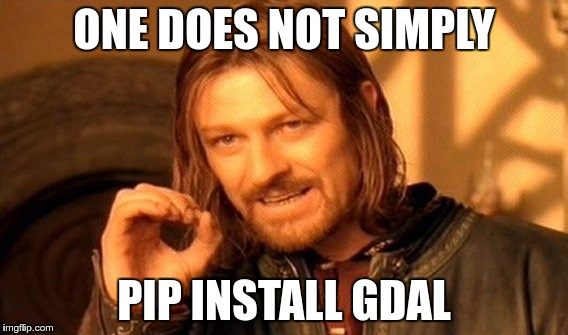

Then they spend three days trying to install GDAL.

“If I can’t install software, how can I code?” — Every student dealing with imposter syndrome

This is how you lose people. Not because the science is too hard. Not because they lack aptitude. But because the infrastructure fails them before they write a single line of code.

This friction isn’t new to data-intensive science. I had similar experiences trying to use GIS on public computer labs with students years ago. Software and tool installation is a reproducibility crisis in disguise.

My crash course in Python’s fragmentation

R came with a safety net

When I worked at NEON building their data skills program, I started building lessons and training materials with R. It was what the ecology community was using at the time AND, it just worked out of the box.

(Does anyone actually put software in boxes anymore?)

The community had built incredible infrastructure. I could send workshop setup instructions, and students would show up ready to learn.

Sure, GDAL was occasionally problematic. But I figured it out.

Python was a different story

My move to Python at CU Boulder was less graceful. Survey data told me the earth science community was standardizing on Python. Industry used it everywhere. Students needed it professionally.

But installing Python packages? That was a nightmare.

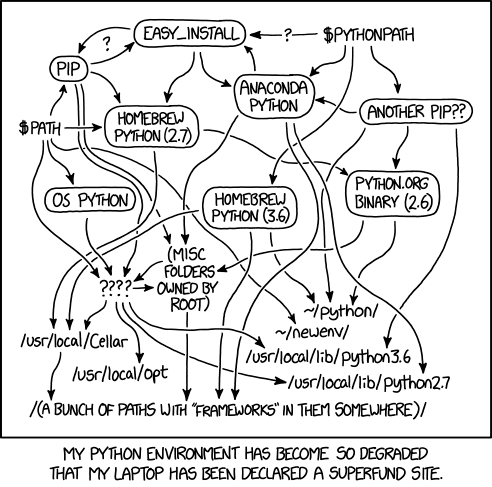

Should I use pip or conda? Which channel—conda-forge or defaults? Wait, mixing them causes conflicts?

I’d install one package. Something else would break. I’d fix that. Something else would fail.

I cried just a little bit getting HDF5 dependencies to install. Forget it. Students trying to install GDAL for spatial data analysis? A nightmare.

GDAL: And tears, lots of tears

Why do you hate me, GDAL? Whyyyyy?

Building a solution: The Earth Analytics environment

I realized this wasn’t just a teaching problem—it was a reproducibility crisis in disguise.

If students couldn’t install packages reliably, how could researchers share reproducible workflows? How could we create open science workflows when the entry point was actually broken?

The breakthrough: Tested, cross-platform environments

Working with colleagues, like my friend Filipe (who created that meme above!), who knew a lot about these topics, I built the Earth Analytics Python environment. The magic wasn’t the environment file itself—it was

- being able to create a lock file that pinned versions of dependencies down and

- being able to test how our lessons ran on different systems in a Continuous Integration environment on GitHub.

We tested on:

- Linux

- Mac

- Windows

Before students even tried to install, we knew where the pain points were. We could troubleshoot before class, not during.

This changed everything.

We used this environment everywhere. In our Docker-supported Jupyter Hub which fueled the hybrid courses that I taught as a part of the Earth Data Analytics Graduate program that I had built.

- We used it in workshops.

- We used it in our Jupyter Hub

- We used it to test each lesson that was published on our open education website (which is no longer but was earthdatascience.org).

Millions of users used our open lessons, built with this environment. Hundreds of students learned Python with it.

What I learned

Environment management isn’t just operations—it’s open science infrastructure.

A tested, reproducible environment means:

- Students spend time learning, not debugging installations

- Researchers can actually reproduce your analysis

- Your future self can return to work months later without starting over

- Scientific tools become genuinely accessible

How this shapes modern practice at pyOpenSci

These lessons aren’t just history—they’re the foundation of how we approach Python education and open science infrastructure at pyOpenSci today.

Locked environments for teaching & learning

When we teach, we use locked environments—typically Docker containers like those that power GitHub Codespaces. Check out our packaging workshop that runs entirely in a Codespace.

Why? Because students should focus on learning packaging, not fighting their local setup. Clear pathways to working environments means they get to coding faster.

The tooling has evolved (The principles haven’t)

Ten years ago, conda-lock was our salvation. Today we have:

And yes pip does them too.

Locking environments is now easier than ever. But it’s just as critical.

The principle remains: If you want your workflows to be reproducible, lock your dependencies. If you’re building applications, lock files aren’t optional—they’re essential. If you’re building software… well that is a bit more complex. More on that another time.

At pyOpenSci, we work directly with maintainers of these tools. We understand that the Python packaging ecosystem is complex, and making it more accessible is an ongoing effort we’re invested in.

When to lock, when to flex

Not every environment needs the same approach:

For teaching: Lock them down if you are in an online environment like JupyterHub. But also, sometimes, flexible environments that resolve to recent, compatible versions can work too. Update them regularly. Test them constantly.

For research workflows: Lock everything when you need someone (including future you) to reproduce exact results. UV and Pixi are great for creating projects with locked environments out of the gate.

For applications: Always lock. Your users need predictability.

For Software: Lock your development environment if you can (especially in CI for security reasons), but don’t lock your package dependencies. Instead, specify compatible version ranges to allow flexibility while avoiding conflicts in user’s environments as they install your package.

The fundamentals: environment management principles

Whether you use conda, pip, uv, or pixi, the core concepts remain the same.

What is a Python environment?

A Python environment is an isolated space containing specific package versions. Different projects can use different versions without conflicts.

Why environments matter for reproducibility

- Isolation: Avoid version conflicts between projects

- Reproducibility: Share exact setup with collaborators

- Safety: Test new packages without breaking your working setup

- Consistency: Ensure everyone on your team or in your lab uses similar or identical environments

The Bigger Picture

Reproducibility doesn’t start when you write code. It starts when someone tries to run your code for the first time. And that someone could be you, months later.

Installation friction isn’t a minor inconvenience—it’s a fundamental barrier to open science. Every researcher who gives up during installation is lost potential for collaboration, validation, and building on your work.

When I founded pyOpenSci in 2018, I brought these hard-won lessons with me. What started as solving installation problems for students evolved into a broader mission: making Python’s scientific ecosystem more accessible to researchers everywhere. The same principles that made our Earth Analytics lessons work—tested environments, clear documentation, reproducible setups—now guide how we support the entire Python open science community.

At pyOpenSci, we’re working to lower these barriers. Through lessons, workshops and events that help researchers build better tools and workflows. We engage directly with the core Python packaging ecosystem to make scientific Python more accessible to more people.

Because open science only works when people can actually access it.