Open education resources for earth and environmental data science

Open education resources, as discussed here refer to lessons that are published online. The goal of publishing such lessons roots in democratizing access - giving anyone with a computer and internet access to learning specific skills. In this case the skills are the ones needed by scientists to develop open, reproducible earth and environmental data science workflows.

Open education resources for earth and environmental data science (and tech in general)

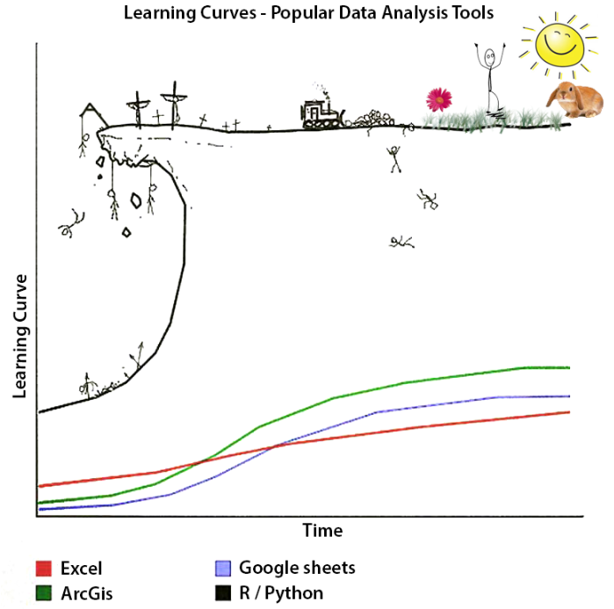

These skills are technical, can have a steep learning curve to learn and often are not available in the form of formal courses at many schools - especially schools serving groups that have been traditionally underrepresented and underserved in STEM.

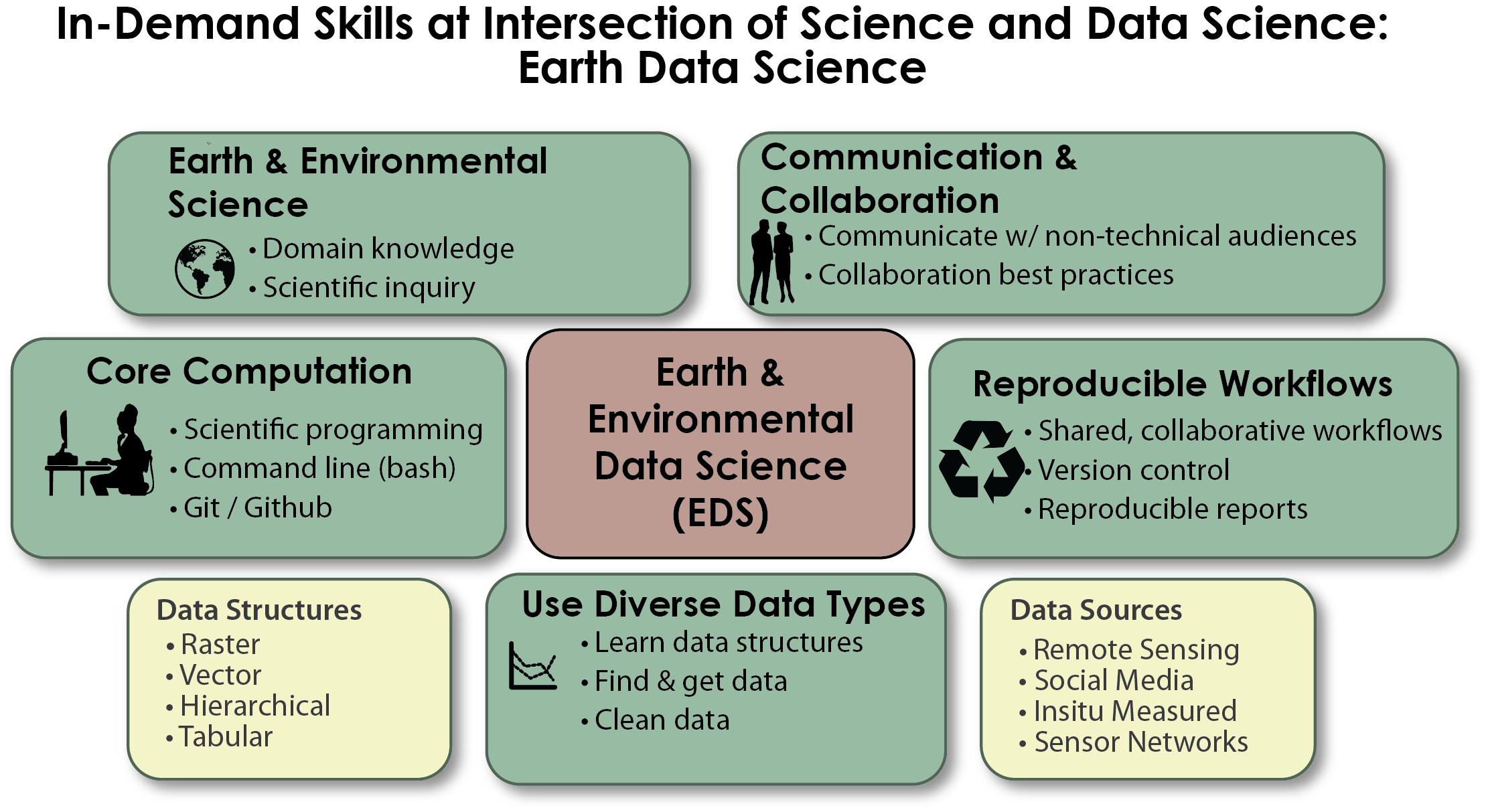

Open education resources for earth and environmental data science are in demand by so many scientists today. And there are millions of jobs available to people with skills that cross the intersection of science and data science

Using Open Source Tools is Also Ideal: Ideally if your online lessons deal with data science, they also have no fees to access them. And no license, or paywalls required to get started with the tools.

But think fast and hard before you decide to publish data science content as open education learning resources

It’s worth considering the end goal of any resources that you publish. If you are publishing earth and environmental data science content, or, any tech content, a one time effort will be short lived in its relevance and usefulness.

Perhaps tech content that is not intended to be maintained over time is better served as a short blog post rather than an open education resource that has a goal of delivering learning content to someone entering or in the field.

Before you publish the content, or even write a grant to create the content, it’s worth considering how long you are able to maintain these resources.

Below I explain why.

Just as tech is rapidly evolving so is data science

The field of data science is rapidly evolving. And so are the tools that support

data processing. In the scientific open source world, versions of Python

change. Ways to process data efficiently change.

All of the open source R and Python tools that make data processing easier in turn require ongoing maintenance.

Open education resources require the same type of maintenance that open source tools do to keep up as the ecosystem evolves.

Some specific examples of how the changing landscape has impacted resources that I have created are discussed next.

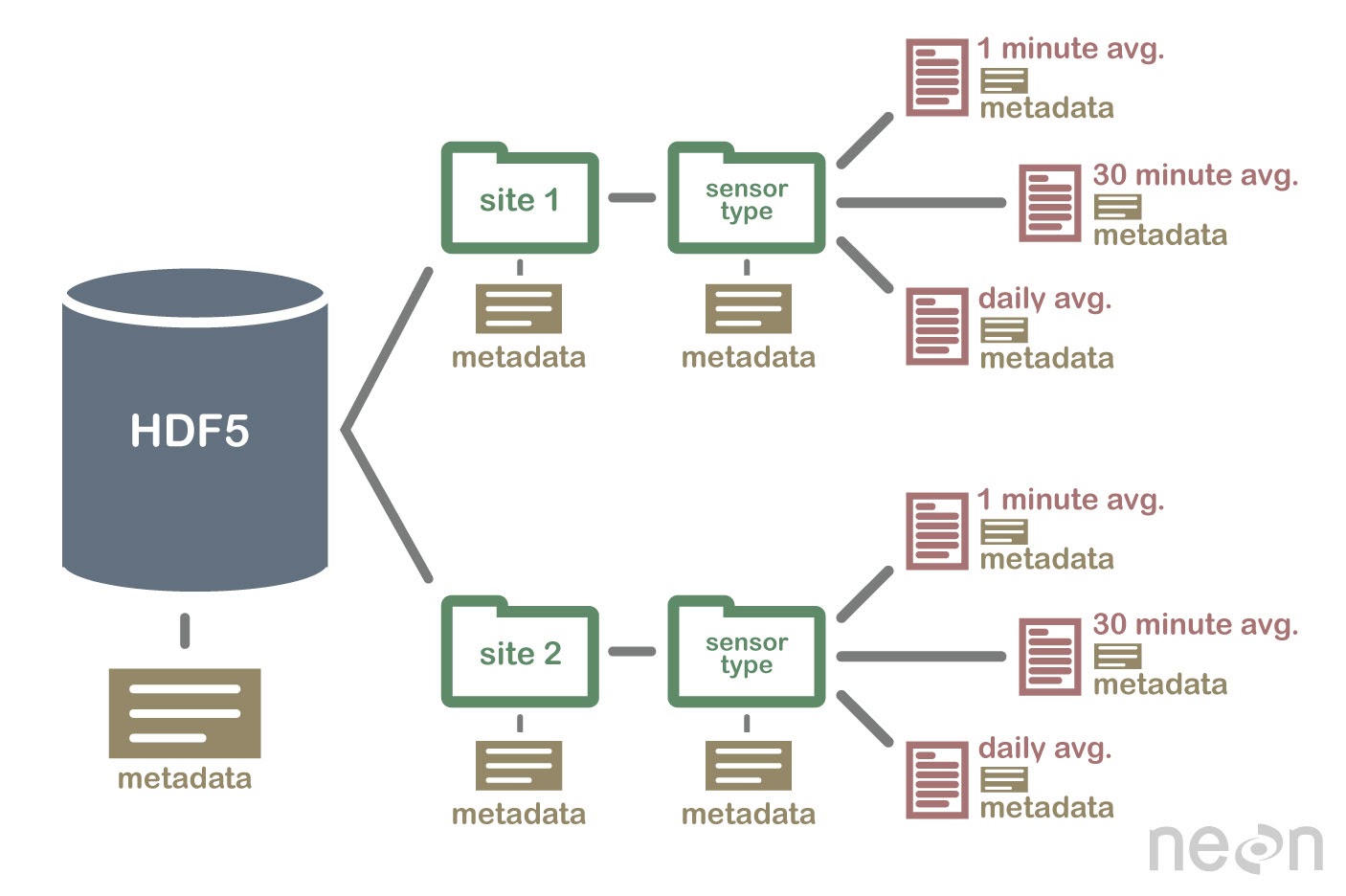

Example 1: Data structures can change over time - an example from NEON hyperspectral remote sensing data

Even in the 5 years that I was at NEON developing data-focused lessons, data structures changed.

Our published suite of lessons on using the hdf5 file format needed to change

because NEON created a new and better organizational structure for the H5 files

that it was sharing with the public during that time.

The hdf5 file format is a hierarchical file format that can store complex data sets

with varying structures. It is the format that NEON delivers it’s raw

hyperspectral remote sensing data in.

This change in data structure meant that all of the online lessons that taught people how to use the data needed to change too. While this takes time it’s ok if you are running a program that depends on the lessons and have the resources to update lessons.

But what happens if you don’t have those resources to update the lessons and they remain online?

Users get frustrated. Waste time fighting with lessons that don’t work. And many (imposter syndrome in science is real) may think they aren’t cut out for data science.

Trends in data science tools used to process data change too

Example 2: base R vs tidyverse

As I was starting to move away from R, discussion of the raster package being

replaced by stars was emerging. And tidyverse was replacing base R as the new

“sexy” and efficient way to do data science.

When I started teaching earth and environmental data science at CU Boulder, I migrated all of my lessons over from base R to tidyverse.

That also took time!

Example 3: Spatial data processing in open source Python

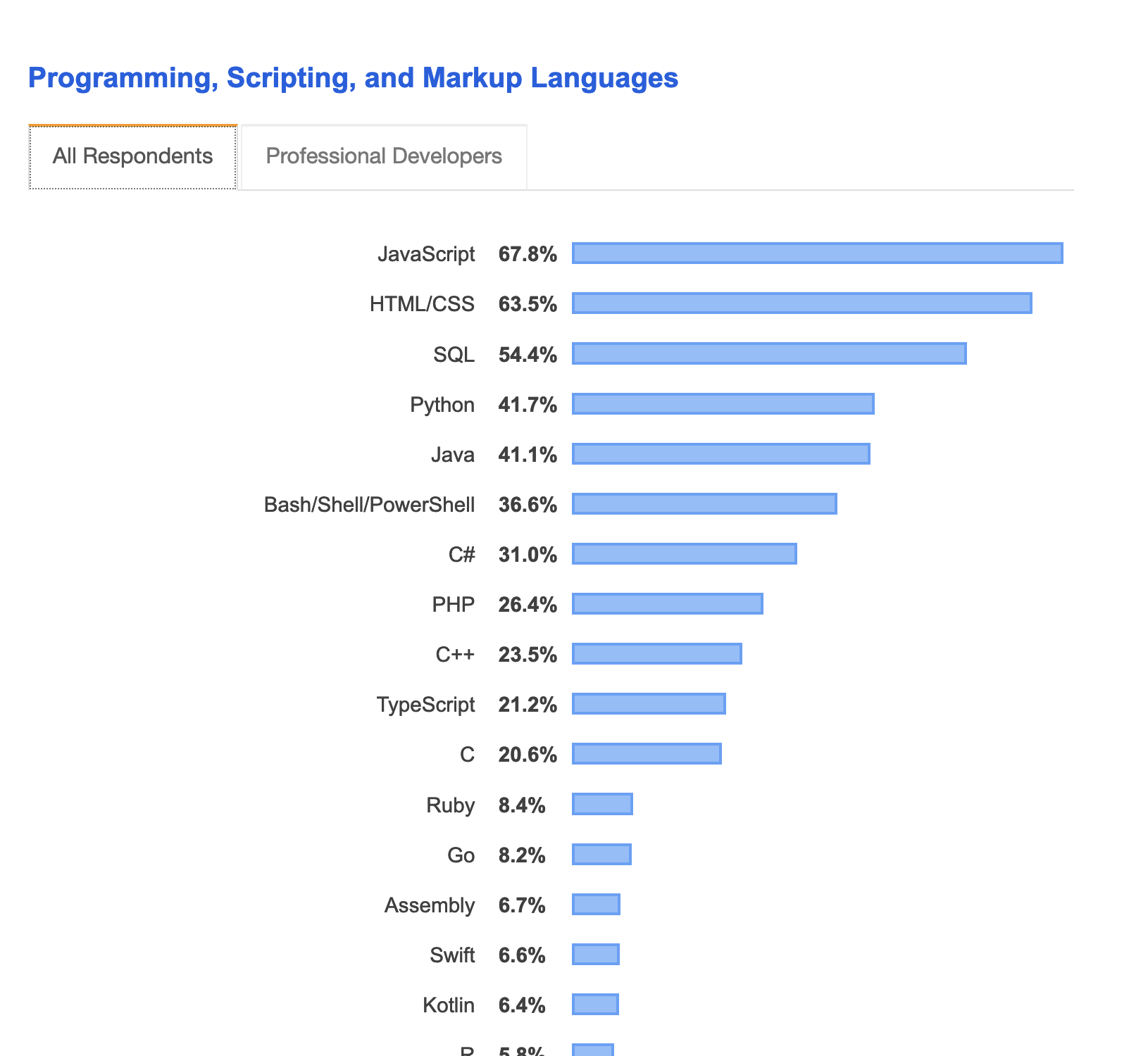

In around 2018 I decided to move away from R and teach Python. Python was more commonly used in the earth science space. It was also more commonly found in industry based on a survey that I lead at the time. Finally, surveys such as Stack Overflow as showed Python as a rising star in the world of development and data science.

In the world of spatial data, back around that time, there was one solid book

on geospatial data processing for scientists in Python. I bought it. As

thorough of a book that it was, it would be the last book I’d buy on technical

approaches to working with data.

This is no dig at the author! Things simply change way too fast.

I needed to build a program that was cutting edge. This book taught spatial data science using core GDAL (an open source tool for processing spatial data). GDAL is profoundly hard to install and learn if you are a beginner. And this approach at the time was probably the best option.

When this book was published, tools like rasterio and xarray, which

removing multiple levels of complexity from raster data processing, were still

in early stagesof development. Or perhaps the author didn’t want to go “all in”

on these tools?

Thus, the code used in the book was much more complex than it needed to be.

# Script to stack three 1-band rasters into a a single 3-band image.

import os

from osgeo import gdal

# Be sure to change your directory.

os.chdir(r'D:\osgeopy-data\Landsat\Washington')

band1_fn = 'p047r027_7t20000730_z10_nn10.tif'

band2_fn = 'p047r027_7t20000730_z10_nn20.tif'

band3_fn = 'p047r027_7t20000730_z10_nn30.tif'

# Open band 1.

in_ds = gdal.Open(band1_fn)

in_band = in_ds.GetRasterBand(1)

# Create a 3-band GeoTIFF with the same dimensions, data type, projection,

# and georeferencing info as band 1. This will be overwritten if it exists.

gtiff_driver = gdal.GetDriverByName('GTiff')

out_ds = gtiff_driver.Create('nat_color.tif',

in_band.XSize, in_band.YSize, 3, in_band.DataType)

out_ds.SetProjection(in_ds.GetProjection())

out_ds.SetGeoTransform(in_ds.GetGeoTransform())

Source: github, last updated Feb 2016

Further, the example code did not follow efficient open reproducible approaches using both:

- hard coded paths and

- repeated code

Here is a similar code example from the textbook that I developed using rioxarray:

# Create the path to your data

landsat_post_fire_path = os.path.join("cold-springs-fire",

"landsat_collect",

"LC080340322016072301T1-SC20180214145802",

"crop")

# Generate a list of tif files using glob

post_fire_paths = glob(os.path.join(landsat_post_fire_path,

"*band*.tif"))

band_1 = rxr.open_rasterio(post_fire_paths[0], masked=True).squeeze()

A conventional textbook was already dated,

This book while great was probably dated when it was published (writing books takes a long time!).

I had hoped to use that published book as my bible for what to teach. Instead I found myself creating my own geospatial lessons in Python text. A text that I could keep current. This online textbook is openly licensed to allow anyone to use the lesson.

The value of online resources, vs. a published book is that online resources can be changed at any time. The downside of a printed book is that it’s pretty darn difficult to modify the contents on the fly.

Anyone could use my textbook lessons:

- In teaching.

- In learning.

- Online.

Example 4: from rasterio to xarray and rioxarray

But alas, my original geospatial data in Python lessons were soon also dated

Ironically, just 2 years after I wrote my first iteration of spatial lessons in

Python, I realized that there were now an even easier set of tools for

students to use. This meant, less code. Less complexity to teach and learn.

And they all centered around xarray, and rioxarray.

This change in our textbooks:

- Reduced the complexity of code needed to process geospatial data significantly!

- Supported students in using tools that would scale as they got into larger data processing (and cloud compute supported processing)

- Made the lessons more relevant and current

In the span of just 3 years, I found 3 different “most efficient approaches” to processing spatial data

What allowed me to keep my lessons current in a way that was different from Garrard’s book (which again was great - I am not critiquing it), was that my lessons were online. Making them easily updatable as the spatial data ecosystem evolved.

My lessons were also published with an open creative commons license which means anyone could use and re-use them. This means that if they become unmaintained, someone else could step in and start to maintain them.

These lessons are unmaintained currently as i’ve moved on to a new position. But perhaps i’ll consider picking up maintenance again in the future (if no one else does). There are many really great spatial libraries out there now to simplify and improve the lessons even more!

Finally, because I was actively teaching these approaches in my courses. Every year, it was my job to keep the content current. People need to get jobs with these skills.

What business model sustains maintained online earth and environmental data science lessons?

After a few years, I had a small team to help me with this effort - which actually is a lot of work. And use of our online lessons grew from thousands of (global) users each month to hundreds of thousands.

Skills, similar to online content, are always more useful when they are current and relevant.

The benefits of creating lessons that supplement an existing, funded program

The benefit of creating lessons that I (and my team) also taught was that:

- Our team would catch issues while teaching; we could then quickly update the lessons.

- Students working through the online lessons in their homework, would also catch and report issues that we could fix (we gave them participation points for identifying bugs or typos in the lessons!)

- Finally, as the tools changed and updated we updated the lessons.

These lessons were more than just a one-time publication of open education resources. They were living resources, that like software or any other technology needed to evolve and be updated as the data-science ecosystem evolved.

Online open education lessons are living documents.

Weekly testing of lessons as the environment updated

To further ensure that our lessons were current and worked, I also developed a weekly automated build that tested each lesson from beginning to end.

While all of this takes a lot of effort. It’s important to consider. If you don’t, you’re just creating another resource that will be obsolete fairly quickly.

At the end of the day this frustrates users.

The problems that I see today in the online data science / open education space

There are numerous challenges today in the online earth and environmental data science open education space

-

Single use blog posts are great but they represent a moment in technology time. It is most likely that these posts will never be updated as that is the nature of a blog post

-

Online lessons and books are being created, through grants and other efforts that are funded for a few years. However there is often no long-term plan to update them as the technology changes. Thus, years are spent developing books and other online resources and in just a few months they can become dated.

-

Lessons are being published with no testing to ensure that they work (in the similar way that you would test software). Thus a user might find a useful resources that simply don’t run on their computer.

Make a plan for updating and maintaining your resources

Data science is quickly evolving. And as such online education resources need to evolve with the times as data and tools change.

If you plan on publishing online lessons, be prepared to update them as those changes happen. This might mean that you publish less content that is higher quality that can be maintained over time.

Or you partner with other groups that have an interest in maintaining high quality content in a collaborative way.

If you can, try to think about these resources as a part of a funded program that you are already working on. Getting funding for maintenance is hard, so write in updates to your content, in any grants or funding that you seek.

What’s next?

How to create a tested online open education portal (and attract millions of global users a year)

In a future blog, I will discuss all of the above ideas in the context of creating the earthdatascience.org website. Earthdatascience.org was built considering all of my experiences with online lessons. This website:

- Had testing infrastructure baked into the publication of lessons that ensured lessons ran end to end prior to going online and there after

- Was funded by a program that

- continually demanded content updates

- incentivized students to identify bugs and issues in the online lessons to enhance lesson quality.

- Was carefully seo optimized to ensure discoverability of content.

Ultimately that site before I left had over 2 million unique global annual users and consistently was returned in google searches.

Stay tuned for more!

Comments?

Share on

Twitter Facebook LinkedInOther articles that you might enjoy...

Why You Shouldn’t Publish Open Education Resources (Or Should You?): Earth and Environmental Data Science

There is a huge number of open education / online tutorials that teach earth and environmental data science skills. However, these lessons will quickly become obsolete as tools evolve. This blog is about why simply publishing a lesson online is not enough.

How I Became an Open Education Advocate for Earth and Environmental Data Science

The idea of Open Education Resources (OER) and the field of earth and environmental sciences are not new. But the terms have become popular in recent years. While I only recently identified with these terms, i've been working in this space for years. Here I talk about how I discovered open education in the context of building online resources.

Three Tips for Building A Discoverable Open Education Website for Scientists

Open Education Resources (OER) referred to lessons and materials that are published online for anyone to use. Here I present a few lessons learned from my experiences.